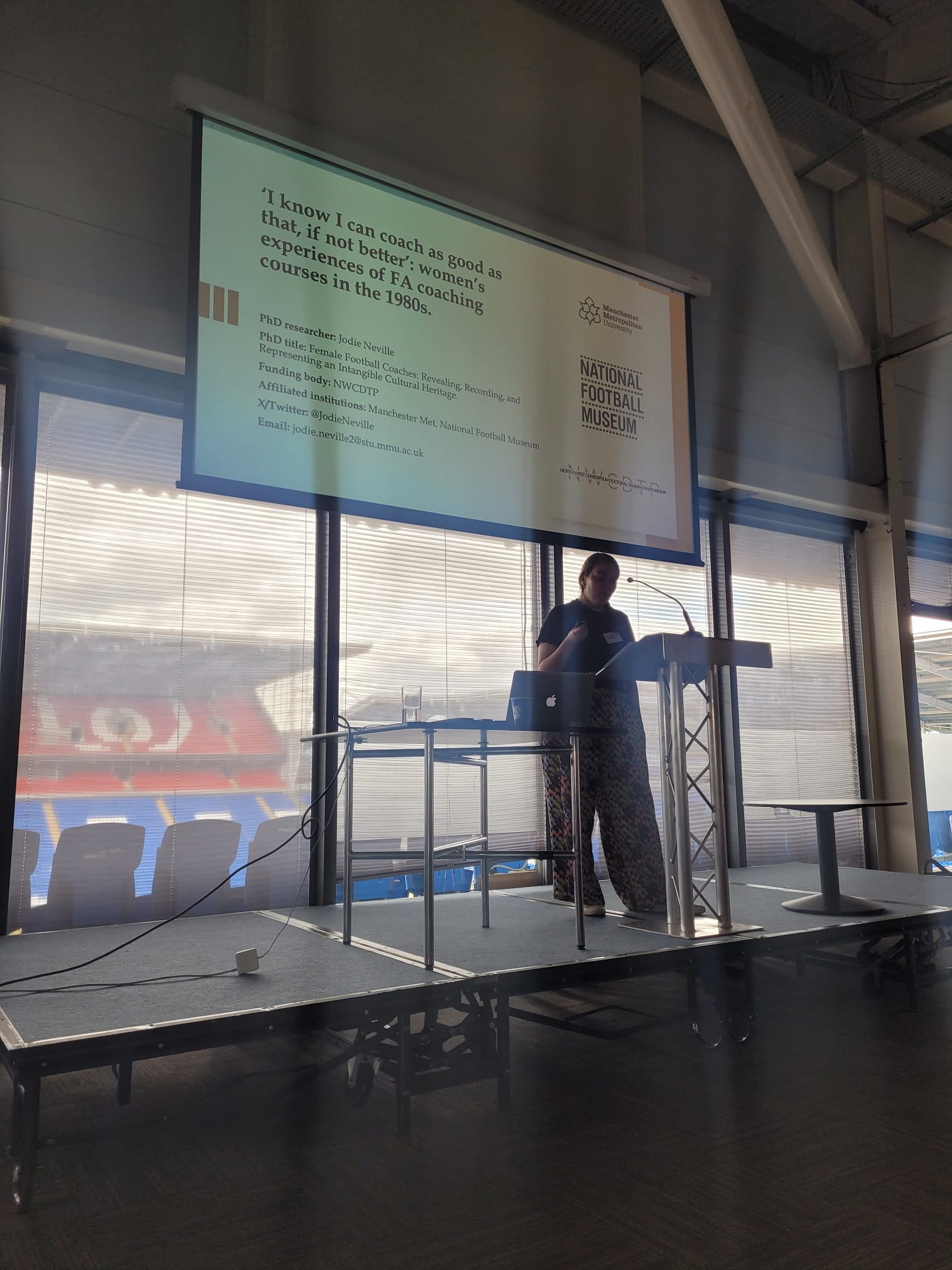

Meet the PhD student: Jodie Neville

In the first of a series of blogs introducing PhD researchers affiliated with Histories of RGSI, Jodie Neville discusses her motivations for beginning her research project, and the historical significance of her work.

Can you tell us a bit about yourself and your background?

My name is Jodie, and I come from a background that blends higher education and the tech industry. My academic roots are in the humanities, my first degrees were English-based, and I’ve always been drawn to how gender is culturally constructed and experienced in everyday life. That interest has followed me throughout my academic and professional career, informing the kinds of questions I ask and the topics I return to. Whether in a seminar, in the workplace, or now in my research, I’m fascinated by how power operates through stories and representation.

In a few sentences, what is your research about?

I see my research as working across two main areas. Firstly, it aims to reveal, record, and represent the experiences of women in football coaching during the twentieth century; voices and stories that have often gone largely undocumented and unheard. Secondly, it explores the social and cultural factors that have shaped or constrained women’s participation in football coaching, using a variety of methods to understand how and why these barriers have persisted.

What drew you to your research topic?

I was drawn to this topic through my wider interest in gender and participation in male-dominated spaces. Having previously worked in the tech industry, which, like football, has historically marginalised women’s contributions, I became increasingly curious about the similarities across different fields. Football coaching struck me as a particularly rich site to explore. Football is popular, visible, influential, and deeply gendered, so women’s stories in that space have often been ignored. That absence becomes even more pronounced when you look beyond players to other roles, like coaching. I wanted to investigate why that is, and what we might learn from the women who’ve done the work, even when they weren’t always recognised for it.

Can you tell us a secret that has made your life as a PhD student easier?

As a working-class, first-generation student, I’ve often felt a bit out of place in academic settings. I couldn’t ask family to proofread essays or talk through seminar readings as attempts to have those conversations would often feel alienating on both sides. Over time, I’ve come to see that background not as a disadvantage, but as a strength. Spending my education looking things up for myself has put me in good stead for undertaking independent research. I don’t expect results to come easily, and I understand the value of hard work. Not being invested in pre-existing hierarchies has meant asking ‘why?’ feels like a perfectly natural question. It has also helped me to relate to my project participants who have also often felt unseen or underestimated.

Your thesis is about women in football coaching. But what other themes does it speak to?

At its heart, my research speaks to broader questions about representation and cultural authority. It asks: who gets to be seen as legitimate in a particular space? And what assumptions underpin that legitimacy? While I focus on football coaching, the themes apply across many fields where certain identities are still treated as the norm. My work looks at how gendered expectations are formed and sustained, particularly through representation, and what happens when women challenge or redefine those expectations.

Why does this history matter today?

This history matters because the gender gap in elite football coaching hasn’t gone away. To understand where we are now, we need to understand how we got here. Looking back helps us identify the long-standing cultural and structural barriers that continue to shape who gets to coach, and why. By listening to the stories of women who have been doing this work, often quietly and against the odds, we can begin to build more inclusive pathways forward.